Art by Mohammed Hanchi

Have you ever made a decision as a community, seemingly embraced by the whole only to be undermined in ways subtle and not so subtle?

When that happens, we often talk about this as resistance. But what is resistance, really? The Cambridge Dictionary defines Resistance as « the act of fighting against something that is attacking you, or refusing to accept something » or as « a force that acts to stop the progress of something or make it slower ». I see the idea of friction, something that holds back, creating a tension. When thinking of working with groups, teams, communities, resistance shows up when a portion of the collective not moving at the same speed or in the same direction than another. A decision may have been taken collectively, yet it is not carried by all. Resistance serves as a powerful expression of disagreement, and is an expression of a conflict that has been either not fully expressed, or worse, silenced.

Like many of us, I am somewhat conflict averse. Yet, over time I have become more and more interested to explore how I can engage with conflict in ways that feel creative and uplift a group’s collective agency. I have also seen how conflicts or tensions that are not fully acknowledged often end up spoiling good collective work. In light of all this, I have become increasingly curious about what my friend Chris Corrigan calls « conflict preservation »: not all conflicts need resolution. In fact maybe most don’t!

Enter Deep Democracy. Deep Democracy has been showing up in my life at different points, but I had never actually crossed the threshold of engaging with it. Until recently, when a workshop was offered in Montreal by Emily Yee Clare and Sera Thompson from the Waterline Collective. One of the many things I find amazing about Deep Democracy is its view of conflict as a source of wisdom that collectives can tap into and approach from a place of curiosity and inquiry, as opposed to something that needs to be eliminated. Deep Democracy was first pioneered by Myrna and Greg Lewis, two psychologists who found themselves practicing in South Africa at the turn of the 1990s, as the Apartheid ended and a new society was emerging. In a context rife with tensions and deep conflictual lines, they hosted hundreds conversations across racial lines where people were able to share their experiences, hopes and perspectives, and explore emerging possibilities. Myrna and Greg Lewis trained others to host conversations, and that is how Deep Democracy spread worldwide.

The first important principle at the heart of this work derives from Arnold Mindell’s work. A psychologist, Mindell was especially interested the unconscious life of groups, and believed that most of their collective wisdom sat in the realm of the unconscious: assumptions, dreams, stories, experiences – elements that are often emotional, emergent, unprocessed. In the same way an iceberg’s emerged surface only shows a small portion of the whole, conscious processes only contain a small portion of the information that is available to help us make wise decisions. When we only access what we can see, understand and verbalize easily, we deprive ourselves of a lot of important information. This is where dialogue processes and good questions become important to bring to the surface this hidden information we carry: unacknowledged, invisible experiences and perspectives, that are often marginalized and made invisible because they carry deep emotions.

But how can we recognize in the first place that there is indeed untapped wisdom, and that some things remain unsaid?

Resistance (and conflict, its close sibling) can act as these indicators that something important might have yet to be said and named and that a decision is being made by the group before it is ripe. Everywhere, resistance tends to get a bad reputation. I cannot think of one time hearing someone say how much they loved being resisted to, or how much they appreciated being in conflict with others. Yet in our work as process hosts, or in our communities, we are often faced with resistance and conflict. They are natural, even healthy parts of life in groups, communities, teams working through change, just as change is a part of life. Often this resistance is seen as something that we need to overcome for a change process to succeed, an innovation to take root, or a new strategy to be embraced, or simply for life to continue. But something in me has never felt quite at ease with this: as if all we needed to navigate this landscape of change was to be more convincing, communicate better, craft better messages, do a better job at selling. I had a hunch that this was not enough, and that by seeing resistance as something to win over, we could be missing out on a whole lot of important wisdom. Plus, I am terrible at selling things.

What if resistance was a pathway to access untapped wisdom in the communities we work with?

What are we resisting to?

Humans are social, yet also fiercely independent creatures. We do not like when decisions are imposed on us. We resist when we feel things are done « to » us, instead of « with » us. Deep down, we want to be part of the change and the decisions that affect how we experience the world and how we live our life. When that opportunity is denied to us is when resistance takes hold. We all have examples, big and small, that talk about this experience of disconnect from the decisions that most affect us: as community members, as workers, as learners, as children. And we also probably have experiences where decisions we made were met with resistance from others affected by it. Any parents reading this? We also probably can all speak about times where undiscussed resistance(s) grew to the point of becoming open conflicts, where work stops, conversations become strained and relationships are damaged, sometimes beyond repair.

How can we recognize resistance for what it is, before it becomes entrenched?

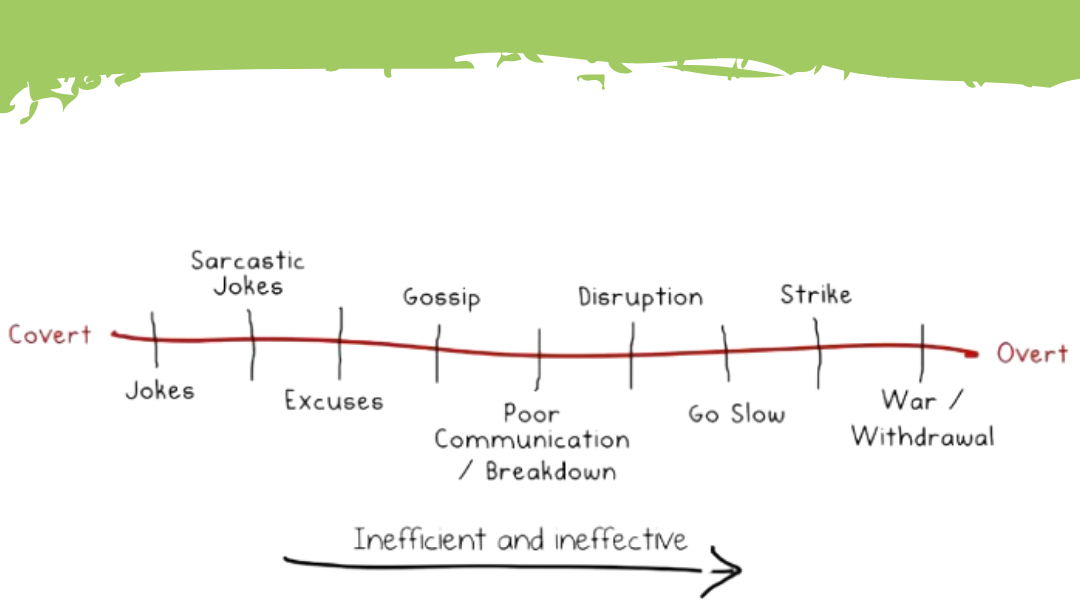

The resistance line is a useful framework that was developed by the Deep Democracy community and that can help us recognize and orient ourselves on the different forms resistance can take in a group. Resistance can be conscious and unconscious. It takes place on a continuum from covert expressions (indirect, subtle, oblique, unspoken, ambiguous) to overt expressions (direct, open, clear, obvious). The resistance line helps us recognize where the group might be on this continuum, which in returns informs the kinds of interventions that are possible and could potentially have an impact. The more resistance is overt, the more it tends to be efficient, and the more work it will take to truly engage with it and invite people to come along. The resistance line can help us know whether we are still in a context where conflict can be addressed by dialogue and other Deep Democracy tools, or whether the environment has become so polarized that other methods of conflict navigation are needed. Think about a group of activists blocking a train line, or a convoy of trucks occupying a capital, or a group of students walking out of their school: it may not be popular, but it is an efficient way to express resistance to a decision or a certain way that things are done. Walking out, however, is usually not the first thing people do when they want to express their opposition to something: chances are that there were multiple other ways resistance was expressed before, that were not heard or did not have the desired impact.

Here are the forms resistance can take in the life of groups, teams, communities:

Image from Lewis Deep Democracy

Like any group process, making decisions collectively is an emotional journey, that happens as much on an unconscious level as it does consciously. As process hosts, we can support groups looking to navigate this emotional landscape by helping them see where unconscious expressions of resistance might be surfaced and made available to the awareness of the group in order to access the untapped, unconscious wisdom present in the group. If we can help the group identify resistance early and have conversations about what unaddressed concerns and needs might lie behind them, we can significantly improve the chances of finding a decision that works for everybody. When we do not, we might let resistance escalate to a point where dialogue becomes impossible: voices have been marginalized beyond repair.

In that spirit, the most impactful intervention we can make as process hosts is to be curious. We can look for the signs of resistance mapped on the line, bring our questions to the group we work with, and invite collective exploration. For instance, if a decision has been taken in the past, but we notice that people are finding excuses to not do something that was previously agreed upon, that may be a good sign that some resistance might be happening. It may be an indication that some early concerns were not expressed, that the context was not ripe for a decision, or that a decision was unilaterally imposed when people should have been given a opportunities to speak their minds. It creates a space for further conversation, where previously untapped wisdom can be invited. When people repeatedly make excuses for something not being done, that could be a sign that something else might be going on, that calls for a pause. It can indicate that it might be time to bring the possibility of resistance to the awareness of the group.

In conclusion, the resistance line is another tool that can be available to us as we navigate our role to help groups, teams, communities better see themselves and what might be going on at both a conscious and unconscious level. It may also be useful to anybody participating in community, to identify early signs that we ourselves may be resisting to something. Is my joke merely a joke, or is it a sign that I may feel uncomfortable about what is happening? And is my discomfort something I can live with, or do I need to bring it up to the attention of my team? All these are good questions to ask ourselves as we strive to participate in communities and practice the joyful and tricky process of humaning together towards a world that can be more joyful, just and welcoming to all.

And if you want to know more about ways to practice on the resistance line, I strongly encourage you to follow the Waterline Collective and check their training offers.